Editing, plus how Kelly Wearstler uses AI, and tips on storytelling from Mia Silverio.

Issue No. 18

Editing

Turn every page is worth a watch. It’s the story of Robert Caro and Robert Gottlieb. Two brilliant people dedicated to making outstanding work (and they often had entertaining arguments). Caro is a fantastic writer, but for me the true hero of that story is Robert Gottlieb. A brilliant and prolific editor. My favorite Gottlieb story is that he renamed Catch-22. Heller had originally titled the book Catch 18, and Gottlieb wanted to avoid confusion with another title and thought 22 was somehow funnier. Which, weirdly, it is.

Editing might seem like an unusual topic for a design newsletter, but if you’re leading design teams, it’s hard not to think about the relationship between generating work and shaping work. It’s very difficult to sit down as a designer and design something alone. The process of design requires outside input. People who might use the product, people who’ve built similar products in the past, people who come at the problem with a completely different perspective. All these inputs are incredibly valuable for any good design process. What’s weird is that we seldom talk about the necessary skills for managing these inputs and turning them into great designs. What to cut, what to include, how to form an opinion, how to express that opinion constructively.

At their core, these skills are the skills of a brilliant editor—someone dedicated to the quality of the work, not the egos of the people involved. There’s a lot we could learn from people like Gottlieb, particularly as editing is getting more and more important.

Time to tap

It used to be the case that an early career designer could become instantly valuable to the team, by turning ideas into tappable prototypes everyone could respond to. I’ve done this myself, capturing ideas from the group discussion and turning them into something more tangible. AI tooling has changed all that—it now takes seconds to turn a thought into something real.

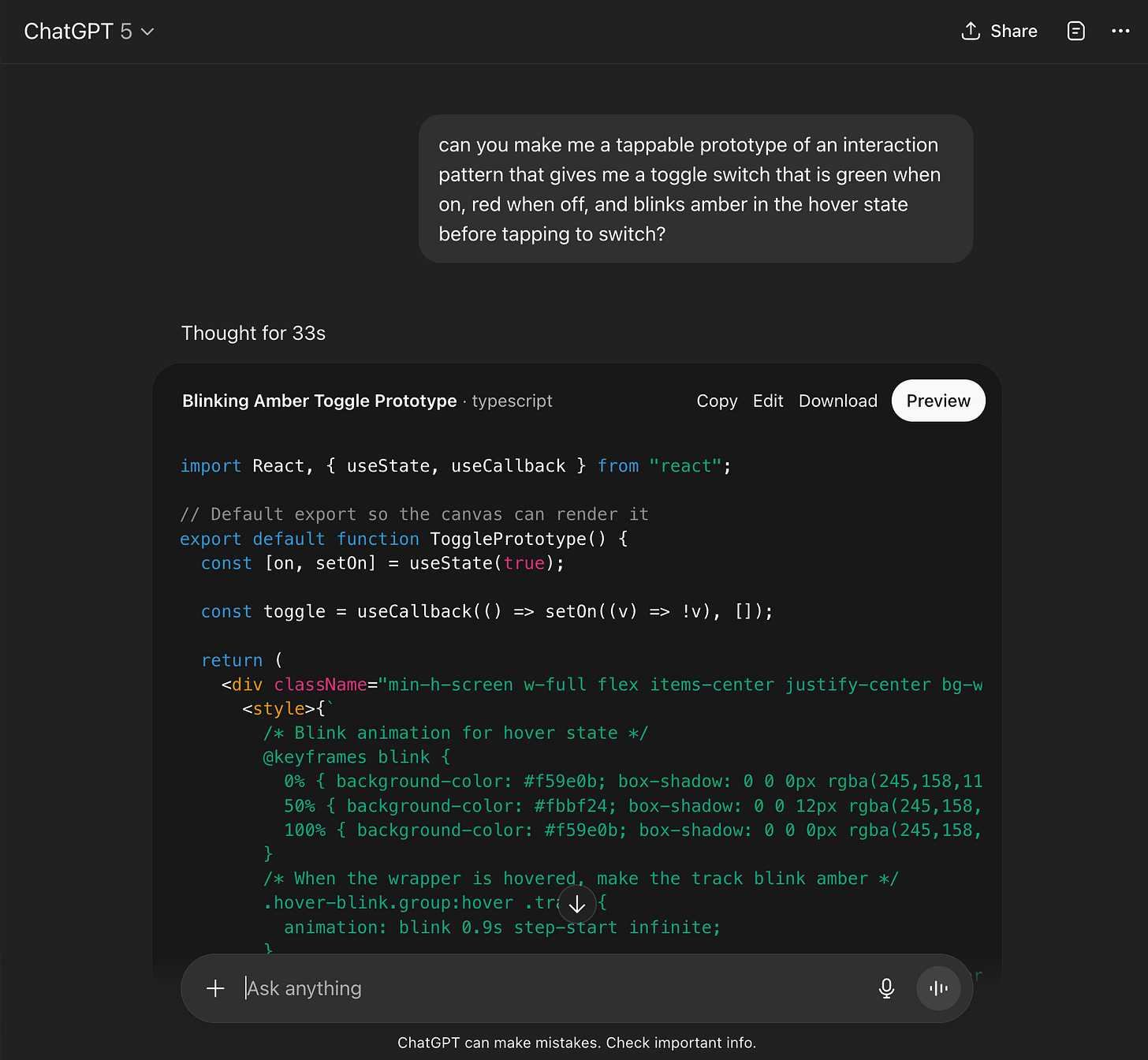

Here’s an example. As I type this sentence I’m trying to think of a small product idea. The type of thing that might come out of a design sprint. Lightweight but worth exploring. Let’s go with a blinking hover state on a toggle switch—something to warn users before changing a high-risk setting. Not my best work, but you get the idea. I’m going to prompt GPT5 to build me a prototype.

It took 33 seconds after I typed the prompt.

So let’s say 60 seconds from thought to tap.

When it’s this easy to prototype, the role of every designer shifts to a more valuable part of the design process. We no longer need early career designers to make the intangible concepts tangible. We need everyone to be shaping the output from an army of design robots. We need people who can combine, discard, and reframe these ideas, moulding them into something truly great.

Creative Directors at fashion houses do this already (minus the robots). Someone like Pharrell Williams can steer menswear at Louis Vuitton by reviewing, combining, discarding and reframing ideas to edit the overall output of the label. It’s part of their working culture to defer to one, singular vision from a human.

This is very different from our collective design process. We use crits and team workshops to refine ideas through consensus, we shape experiences with data, we refine concepts by testing them with real people. Our work culture is at odds with our new reality—consensus, data, testing—these are things robots do better than humans, and things Pharrell doesn’t do at all.

Edge of an editor

The more I learn about Gottlieb, the more I see echoes of his wisdom in our industry.

Remember the reader

“An editor is someone who notices when the writer has lost the reader.”

I love the way he frames the challenge here: there’s no blame. It’s not adversarial. He acknowledges that it’s very common and quite understandable that a writer may lose the reader.

If your experience of working in close partnership with PM and Engineering is anything like mine, this will resonate. Nobody intends to lose sight of the person who’ll ultimately use the product, but it often happens. Design is the voice of the user—but I love this extension: that design helps the team course-correct when we’ve lost sight of the person we're building for.

Cut without mercy, but with care.

When Caro turned in his million-word draft, Gottlieb said:

“Bobby, it’s too long. You have to cut it by the length of a book.”

Caro asked, “Which book?” Gottlieb replied:

“Take your pick.”

This, to me, is one of the hardest parts of seniority: getting comfortable with how much good thinking you leave behind. If you’re lucky enough to work with brilliant people, it’s very rare that you’ll be choosing between a good idea and a bad idea. A more common scenario is that you’ll have different types of great ideas. Competing consequences, divergent implications. Add to that the human aspect of leading a team or project and being the person who has to make the decisions—I can’t think of a better credo than without mercy, but with care.

Trust your instincts

“I don’t have a theory of editing. I just read the thing and see what works and what doesn’t.”

I love this. At its core, Gottlieb sees editing as a natural response to something someone created. It’s wonderfully subjective.

By contrast, I think there’s been a sustained effort to make design (and any type of commercial creativity) a more objective practice. Data, rapid feedback loops, user testing. These are ways to remove the subjectivity from our practice (often a good thing), but there’s a tension here, between the head and heart of design.

I love that Gottlieb was able to demonstrate so much rigor and dedication to the reader, but balance that with his own instincts on the work. Something I suspect will become more important for all designers over the next few years.

If you watch the documentary, I’d love to hear your thoughts. I loved the intensity of Gottlieb’s approach, but was also amazed by how much he cared. For Gottlieb editing wasn’t part of the process, it was a unique opportunity to turn something good into something spectacular. In a world where ideas can be turned into prototypes in a few seconds, we need that same belief—that our judgment—our ability to edit the output of very capable robots will become the only true differentiator for any successful design team.

What an amazing time to be a designer an editor.

A drop of links to keep the signal strong. Videos, essays, books, oddities. Anything I find that’s worth sharing. Email sam@readwireframe.com with any suggestions.

Kelly Wearstler wrote about how she uses AI in her studio. For creative types struggling to be inspired by AI tooling and how it can push the creative process—it’s worth a read. It’s for paid subscribers, but access to Kelly’s newsletter is worth it.

Mia Silverio is part of the Prof Galloway crew and wrote a wonderful piece on storytelling. It’s perhaps best summed up by a Derek Thompson quote at the top of the piece: “There’s something overlapping in the Venn diagram between what is demanded of standup comics and what is demanded from public intellectuals. And that is: Explain this shit to me — make me feel something.”

If (like me) you don’t understand what quantum computing is, but know it’s going to be incredibly important—you might find this explanation by Dr. Michio Kaku useful.